Nothing ever moves quickly in litigation. Of course, it’s complex, technical and necessarily procedural with challenging timetabling demands placed on the judiciary but there are other factors too. Legal services rely on monetising time through hourly rates that discourages efficiency. Other times, the judiciary can be slow on its own admission, for example in Bilta v Natwest Markets plc, where the Court of Appeal described the 19 months taken to hand down the first instance judgment as “inexcusable” as a result of which a re-trial has been ordered.

Businesses involved in litigation may bemoan the general snail’s pace of litigation and the resulting untold costs but successful commercial entities are also nimble and savvy enough to take advantage by arbitraging this time to create value and profit through what is effectively a corporatised form of “receive now and pay later”, or in layman’s terms, “do wrong and receive the benefits now, and worry about paying the consequences of it later”.

This is the arbitraging of the time value of litigation, a concept which everyone understands in the abstract but which this piece illustrates in mathematical terms using the same principles of the time value of money.

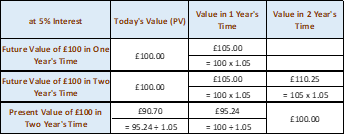

Understanding the time value of money

The time value of money is the concept that the value of £100 today is worth more in the future than it is today. For example, if we assumed interest rates were 5%, we would know that £100 today would be worth:

- £105 in one year’s time, being [£100 x 1.05]; and

- £110.25 in two years’ time, being [£100 x 1.052].

Conversely, it follows in reverse that £100 in two years’ time would have a Present Value (PV) of £90.70 today, being [£100 ÷ 1.052].

This basic principle of present valuing is used extensively to calculate the value of any future cashflow arising from an action taken today, including those taken in litigation proceedings.

Example 1: To honour or not to honour

Imagine being the management of a corporate that owes a third party a £10 million fee for completing a transaction. The management’s obligations are to deliver shareholder value and maximise profits so it arrives at two options. It can either:

- Honour the contract; or

- Breach the contract so that it keeps £10 million and book it straight to P&L on the basis that it might have to pay that amount later.

A typical legal analysis would say that breaching the contract (2) has less commercial value because it will have to pay the £10 million in any case, plus the costs of litigation plus any other reputational and transactional costs to its future operations. However, looked at financially, that doesn’t hold.

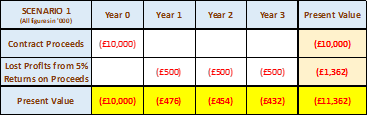

Table 1

Table 1 above shows how by honouring the contract and paying £10 million, the total cost over three years would be:

- The £10 million paid out today which has a PV cost of £10 million; and

- The annual 5% return on £10 million (being £500,000 per year) which could have reasonably been earned if the £10 million was invested elsewhere into the business (effectively the loss of chance for that £10 million). Over the three years, this has a PV cost of £1.4 million*.

The total PV cost of honouring the contract (1) is therefore £11.4 million, being the sum of the two PVs above.

Contrast that to breaching the contract (2), illustrated in table 2 below.

Table 2

This shows the various costs incurred over three years by breaching the £10 million payment including having to pay the £10 million eventually by way of damages after three years of litigation. The costs would be:

- £1.5 million of gross legal costs, which has a PV cost* of £1.4 million;

- £10.0 million damages ordered in three years’ time, which has a PV cost* of £8.6 million; and

- £1.0 million adverse costs ordered in three years’ time, which has a PV cost* of £0.8 million

… the sum of all three being £10.9 million.

In other words, on the same “receive now, pay later” principles of present valuing, the actual PV cost of breaching (2) is £10.9 million, which is less than the £11.4 million PV cost of honouring (1) the contract.

(A full analysis would also probability-weight the prospects of the litigation, which is not covered in this piece. However, one cannot ignore the possibility that the third party may not even pursue the action in which case the best-case scenario for the PV cost of breaching (2) is £0.)

The choice then that management must make is between:

- Scenario (1) (honour) which costs £11.4 million in PV terms, or

- Scenario (2) (breach) which costs £10.9 million in PV terms which could also cost £0.

The decision is therefore straightforward – Scenario (2) (breach) is a cheaper and more attractive route for management to pursue.

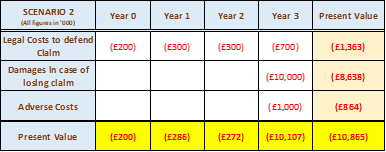

Why time is so important

Time creates the opportunity to arbitrage because in simple terms, the further in the future a cashflow is, the less value it has today. To illustrate this, we change our assumptions so recourse through litigation only takes one year.

In Table 3, we play out honouring the contract (1) again but over one year. The total PV cost over one year is now only £10.5 million*, down from £11.4 million.

Table 3

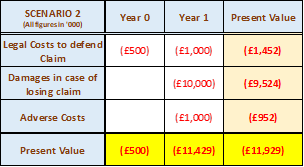

When we play out the breaching scenario (2) also over one year as illustrated in Table 4, we can see the PV cost of breaching (2) increases to £11.9 million*.

Table 4

The management now have a very different decision to make, between

- Scenario (1) (honour) that costs £10.5 million in PV terms, or

- Scenario (2) (breach) which costs £11.9 million in PV

While breaching (2) could still be as low as £0, honouring the contract now looks far more attractive than before because the quicker litigation process means there is less commercial value in not honouring the contract (1). This makes arbitraging the time value of litigation less attractive.

Example 2: The delaying tactic

Now consider a large, listed corporate facing a potential liability of £5 billion for a wrong-doing which has already been established. The corporate arrives at two realistic options (we discount the option of just paying the £5 billion liability upfront). It can either:

- negotiate a settlement at significantly less than the £5 billion, or

- delay and arbitrage the time value of litigation.

Any settlement (A) will not only take into consideration the hit on P&L, share price and reputation (which we ignore for the purpose of this illustrative exercise) but the actual funding cost of borrowing the money required to pay the settlement.

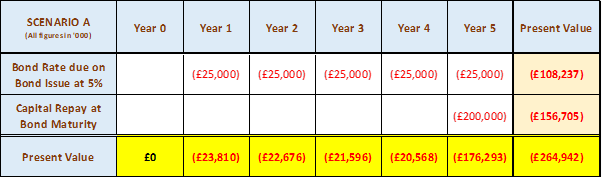

Let’s assume a settlement amount can be negotiated at 4% of the headline claim value (being £200 million) and this is funded via a five-year £200 million bond issue with a bond rate of 5% per annum, as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5

By present valuing the annual interest payments of a 5%-yielding five-year bond with capital repayment at the point of the bond maturing in year 5, the PV cost would be £264.9 million*.

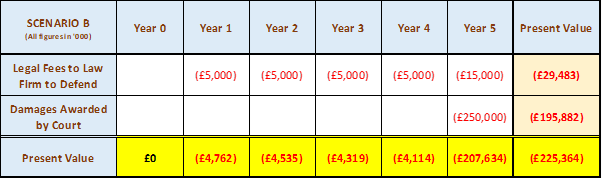

We then compare this to the PV cost in Scenario (B) – the delaying tactic, whereby a high-powered law firm is instructed to run the claim with a mandate to both delay and attempt to seek a lower damages outcome. Let’s assume the law firm actually takes it all the way to trial and the corporate is ordered to pay damages at £250 million, more than the £200 million negotiated settlement, in five years’ time, as shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6

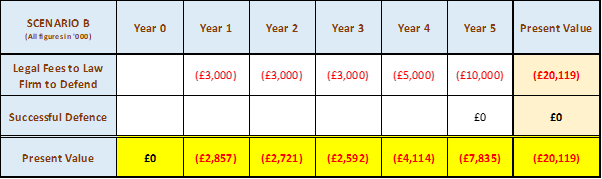

Even though the £250 million damages awarded is greater than the £200 million settlement, the PV cost of delaying (B) is £225.4 million*, significantly less than the £264.9 million PV cost* of settlement (A). Put another way, the legal costs are a cheaper form of debt financing than the cost of debt itself. And of course, there is the possibility that clever lawyering might reduce this significantly, perhaps even to £0 (think Lloyd v Google) as illustrated in Table 7, where the PV cost could end up being only £20.1 million.

Table 7

The choices for the corporate are then:

- Scenario (A) (settle) with a PV cost of £264.9 million, or

- Scenario (B) (delay) with a PV cost of £225.4 million which could actually be as low as £20.1 million.

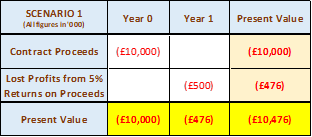

Why time is important

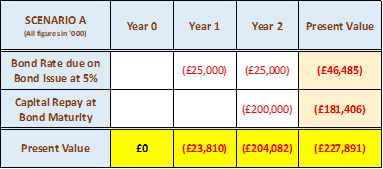

We now analyse what happens if we reduce the five-year timeframe to two years. Table 8 shows that with the funding cost of a £200 million settlement, the PV cost of settlement (A) reduces to £227.9 million*.

Table 8

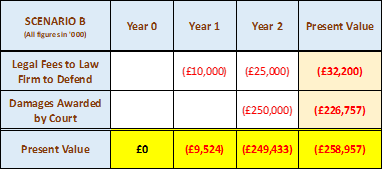

However, when we do the same in the delaying tactic scenario (B) as illustrated in Table 9, we can see the PV cost increases to £259.0 million*.

Table 9

The management now therefore have a very different decision to make, between

- Scenario (A) (settle) which costs £227.9 million in PV terms, or

- Scenario (B) (delay) which costs £259.0 million in PV

Again, we can see how the quicker the litigation process, the more attractive it becomes to settle rather than to delay and engage in gameplay, making the arbitrage of the time value of litigation less attractive for a defending corporate.

Conclusions

This high-level illustrative analysis does not pretend to capture the nuances of each litigation, nor the financial circumstances of a defending party, nor all the assumptions that should go into a comparative financial model. However, what it shows is how much the speed of litigation can give defendants the opportunity to arbitrage the time value of litigation.

Bigger picture, it also shows how slow legal proceedings inadvertently hinder access to justice as well as arguably encouraging the wrong-doing that leads to so many of the causes of action that we see in the market. This is something that policy makers should be aware of when considering how one can improve access to justice.

* Assumes a 5% discount interest rate.