The 2021 Guideline Hourly Rates (GHR) for solicitors came into force on 1 October 2021. What does that mean? Champagne and oysters for those receiving costs? Poverty and penury for those paying costs? As with most things legal, it is not as clear cut as that!

To start with, what are the GHR and why are they important? The answers are that from about 1990, it became the custom to calculate solicitors’ costs by reference to hours spent multiplied by an hourly rate, replacing earlier anecdotal methods such as measuring the depth of the file with a ruler or weighing it on scales as if the work undertaken was a bag of flour.

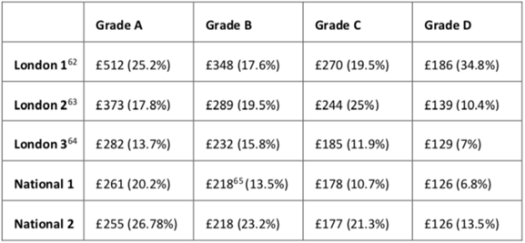

The expense of time method of charging was not without its critics. When he was Master of the Rolls, Lord Neuberger commented in 2012 that “hourly billing fails to reward the diligent, the efficient and the able…”. However, by then rates in the form of tables were available, with fee earners being graded A-D according to experience, with their charges being dependent upon where their firm was located, London “City” being the best remunerated and Band 3 “National” being the least. Although these were supposed to be rates to assist judges when they carried out summary assessments, they effectively became the starting point for any judicial quantification of costs, including detailed assessment. For that reason, the GHR have assumed considerable importance over the past decade, with much noise being made that they have failed to keep up with inflation.

Although an attempt was made in 2015 to review the rates following work undertaken by the Foskett Committee, the recommendations were rejected by the then Master of the Rolls, Lord Dyson, so dust gathered on the hourly rates until 2020, when a Civil Justice Council (CJC) Working Group was set up under Stewart J. The CJC published its final report on 30 July 2021. This time – success. On 16 August 2021, its recommendations were accepted by Sir Geoffrey Vos, the current Master of the Rolls, and the latest guidance about what rates to allow from 1 October 2021 can be found in the recently published Guide to the Summary Assessment of Costs (the Guide) (the percentage increase on the 2010 rates appears in brackets).

At paragraph 28, the Guide says:

“The guideline figures are intended to provide a starting point for those faced with summary assessment. They may also be a helpful starting point on detailed assessment”.

So far, so clear, but it is important to remember the GHR are just that, guidelines and that uplifts can be achieved depending on other factors.

Paragraph 29 says:

“….the value of the litigation, the level of the complexity, the urgency or importance of the matter, as well as any international element, would justify a significantly higher rate”.

It is to be inferred, therefore, that the GHR are the starting point, and a party receiving costs will not recover less on assessment, except if a lower rate has been agreed with the client which would infringe the indemnity principle. However, that may no longer be a safe inference to draw.

Although the 2021 rates were not supposed to apply until 1 October 2021, the reality is that there has been a certain amount of jumping the gun. Miles J appeared to do so in ECU Group plc v Deutsche Bank (at paragraph 26), and HHJ Matthews unquestionably did so in Axnoller Events Ltd v Brake, but in this latter case, with outcomes that can only be described as questionable.

In Axnoller, the court was addressing the costs incurred in relation to two applications which had occupied the court for one day. The judge directed that the costs be summarily assessed and had given directions for the filing of schedules and submissions, so that the assessment could be dealt with on paper. The receiving parties can conveniently be called “the Guys” and the paying parties, “the Brakes”.

The Guys’ schedule sought £68,729. Of that sum, in dispute between the parties was whether London solicitors had reasonably been instructed in a case proceeding in Bristol, whether their rates were reasonable, whether it had been reasonable to brief leading counsel, and whether the hours claimed had been reasonable.

In reaching his decision, the judge said:

“I accept that the 2010 summary assessment guidelines are now well out of date. In a case like this, I would simply put them on one side as of little assistance. Although they are strictly speaking not yet in force, the new 2021 guidelines (which have been approved by the Master of the Rolls) have already been used in summary assessment in the High Court: see e.g. ECU Group plc v Deutsche Bank ….[25]. I consider that I should take these guidelines into account.”

The judge then went on to make the following findings:

- It was reasonable to retain London solicitors since a property at the centre of the dispute was worth several million pounds, the facts of the case were complex, and parts of the claim were legally complex.

- The hourly expense rates were well over the top even for London firms, with all fee earners except the trainee solicitor and the costs draftsman being charged at more than £100 an hour in excess of the top 2021 GHR for very heavy commercial and corporate work by a centrally based London firm; the work did not justify anything in excess of that rate. “If anything, it justifies less” he said.

- The total number of hours recorded were surprisingly high, even for a document heavy application.

- There was nothing unreasonable or disproportionate in the employment of both leading and junior counsel on an application of the type in question.

Having made these findings, it might be expected that the Guys would have done reasonably well out of the summary assessment. True, the hourly rate would take a hit and there would have been an adjustment for the hours spent, and as Henshaw J observed in DVB Bank SE v Vega Marine Ltd :

“Summary assessment [was] not intended to be a 100% costs recovery regime”(paragraph 31).

However, the Guys had won on both retaining the London solicitors and on retaining counsel. In addition, they would have been reassured by the judge’s comments that the litigation as a whole was peculiarly wide ranging, factually complex and, at least in part, legally difficult, and that one of the applications had involved a wholly new area of law.

What then, could the Guys expect to recover even though the costs were being assessed on the standard not indemnity basis ? A 10% reduction would be £62,000 (rounded up) and a 15% reduction would be £58,400 (rounded down).

The judge’s figure was £25,000 for the solicitors (instead of £40,000) and £15,000 for both counsel (instead of £20,000, plus some disbursements of £948 (a court and transcriber’s fee), totalling £40,948, meaning that the reduction was over 40%. Given that the judge had used the 2021 GHR, this would not have been a happy day in court for the Guys. Imagine the solicitors having to explain that although they had won the application, the Guys were going to be out of pocket to the tune of nearly £28,000! (In fact, it was more, as the judge had ordered the Brakes to pay just 50% of the costs, but that does not matter for the purposes of this blog.)

What are the lessons and what food is there for future thought?

The starting point is that although judges receive training in costs assessments through courses run by the Judicial College, outcomes can be unpredictable, as Axnoller has shown. Summary assessment can be, and often is, rough and ready justice, with none of the niceties of detailed assessment where the reasons for incurring the costs can be deployed using fully focussed arguments. Frequently, however, summary assessment takes place at the end of a long day, when the judge, the advocates and the parties simply want to get home.

Therein lies the potential unfairness; using a blunt instrument such as summary assessment after a hard court day can lead to loss of fairness for both sides, but at least there is an opportunity for oral submissions. In Axnoller there was none because the job was done on paper, all the more reason for the Guys to ask: if we won on using London solicitors, deployment of the 2021 GHR and on counsel, how on earth did we end up losing 40% of our costs?

If there is an answer to that question, it is first that the judge should not have allowed less than the GHR as they are the starting point (paragraph 28 of the Guide). Secondly, having made findings about complexity, value and suitability for London solicitors, the judge should have allowed more. Thirdly, having found the case fit for a leader, he should have awarded a brief fee that befitted a leader, rather than by chopping down the fees by 25%. Finally, although the situation is better than it used to be through the Judicial College courses, it cannot be taken for granted that costs are the first string to the bow of the judge who hears the case.

Next time (if there is a next time) for the Guys, what about using PD 44.9.2(b) to CPR 44.6? If there is “good reason” for the costs not to be dealt with summarily (for example where, as there was here, the costs are large and involve the contentious issues set out above), the matter can be dealt with by a payment on account under CPR 44.2(8) and an order for a detailed assessment, so that there is no loss of fairness to either party, whether paying or receiving.