When Guideline Hourly Rates (GHR) came into force, they did so with the directive that they be “used as a starting point for judges carrying out summary assessment of costs” (Civil Justice Council’s Annual Report 2019-2020) and that “these guideline rates are broad approximations to be used only as a starting point for judges carrying out summary assessment.”

Whilst the notes in the White Book refer to the fact that “a rate in excess of the guideline figures may be appropriate”, these decisions demonstrate a worrying trend that it is becoming increasingly difficult to persuade the courts to depart from the GHR.

There have recently been three significant decisions concerning GHR recoverable between the parties.

The facts of these cases could not be more different but Master Rowley, Lord Justice Males and HHJ Paul Matthews (sitting as a High Court Judge) each determined that the GHR was the correct starting point and that departure from the GHR was by no means a foregone conclusion.

The cases are:

- R v Barts NHS Trust [2022] EWHC B3 (Costs), where judicial review proceedings in relation to a parents’ application for their daughter, who sustained a severe brain injury, to be transferred to another country for treatment and for which the defendants wanted to withdraw treatment.

- Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd and others v LG Display Co Ltd and others [2021] EWHC 1429 (Comm), which involved an application to set aside an order granting the claimants permission to serve the defendant out of the jurisdiction in Taiwan and Korea in relation to an infringement of article 101 of the Treaty on the Function of the European Union (TFEU).

- Rushbrooke UK Ltd v 4 Designs Concept Ltd [2022] EWHC 1416 (Ch), which involved an application by the claimant company for an injunction to restrain presentation of a winding-up petition.

In Barts, Master Rowley applied the Wraith v Sheffield Forgemasters test [1997] 2 Costs LR 74 and determined that the instruction of Manchester solicitors by a London client “can hardly ever be any criticism of a receiving party who instructs solicitors in a less expensive area of the country” (paragraph 42, judgment).

With regard to the second stage of the Wraith test: was the hourly rate itself reasonable? Rowley determined that the GHR was the correct starting point but rejected the submission, on the facts of the case, that the receiving party’s solicitors had passed the “baton of responsibility to counsel” such that no skill, effort or specialised knowledge was exercised by the claimant’s solicitors themselves (paragraphs 45 and 55, judgment).

Whilst Master Rowley concluded that he was allowing the rate as claimed, this did not mean on assessment he would not reduce counsel’s fees or the solicitors’ time.

In the Samsung decision, Males LJ made specific reference to the fact that the London GHR had been set “already assum[ing] that the litigation in question would” be “very heavy commercial work” but Males LJ concluded that to depart from the GHR a “clear and compelling justification must be provided”(paragraphs 4 and 6, judgment).

In Rushbrooke, HHJ Matthews determined that whilst GHR were “of course merely guidelines …they represent a consensus view of what average work should cost in particular areas of the country” but saw “nothing in this present case to suggest that the work […] was above average in difficulty, or in complexity, or in novelty, or in importance to the client” such that a 34% departure was considered to be “too high” (paragraph 13, judgment).

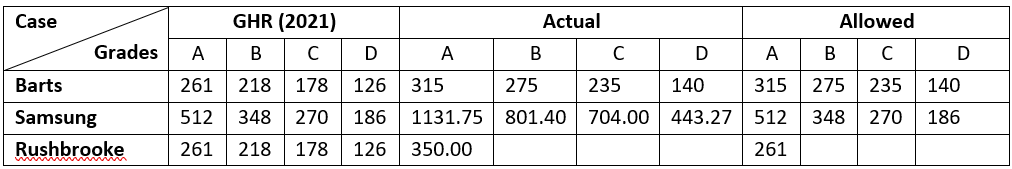

The rates charged in these three cases were as follows:

So how do solicitors persuade the courts to depart from the GHR?

1. Avoid summary assessment (PD 44.9.2)

Summary assessment is a not a “’line by line’ exercise, but much more ‘broadbrush’” (paragraph 15, Rushbrooke) so if this can be avoided then the blunt instrument of summary assessment is immediately avoided.

2. Obtain an indemnity basis costs order (CPR 44.3(1)(b))

An indemnity basis costs order has the benefit of shifting the emphasis of reasonableness, such that if there is any doubt it is resolved in favour of the receiving party.

3.Justification (CPR 44.4(3))

The complexities of each case should be advanced in any costs submissions by reference to the following pillars of wisdom that the court will have regard to, namely:

(a) the conduct of all the parties, including in particular –

(i) conduct before, as well as during, the proceedings; and

(ii) the efforts made, if any, before and during the proceedings in order to try to resolve the dispute;

(b) the amount or value of any money or property involved;

(c) the importance of the matter to all the parties;

(d) the particular complexity of the matter or the difficulty or novelty of the questions raised;

(e) the skill, effort, specialised knowledge and responsibility involved;

(f) the time spent on the case;

(g) the place where and the circumstances in which work or any part of it was done; and

(h) the receiving party’s last approved or agreed budget.

The courts will not allow any departure from GHR without such submissions to include any area of specialism the practising solicitor may have.

4. Teamwork/Delegation

“One of the important skills of a solicitor is to know how to delegate less important work to less expensive fee earners” (paragraph 14, Rushbrooke).

The courts clearly wish to see where appropriate delegation to lower grades of fee earners, demonstrating a pro-active approach to costs management. That said, caution must be exercised in, for example, over delegating to counsel such that the courts consider the “baton of responsibility” for the case has been passed to counsel to the extent that no skill or expertise is deployed by the conducting solicitor. The courts need to see “very much a team effort between solicitors and counsel in terms of communication with other parties, the drafting of documentation, the strategy and so on” (paragraph 54, Barts).

The way forward

Without adopting these practices (and ensuring counsel is adequately briefed), this could end up being a very costly omission. Recently, I am aware of the Samsung decision biting in a Manchester commercial litigation costs case resulting in a claim for costs being reduced, on summary assessment, from £31,000 down to £13,000; that is going to be a difficult conversation for the solicitor to have with his client. How do you adequately explain the idiosyncrasies of our judicial system particularly in relation to the costs, with your client?

Such a decision putting more emphasis on and indeed these days, no article on costs can be complete, without emphasising the importance of ensuring that you have obtained your client’s informed consent.

In the context of the GHR, the client must be informed of the rates charged if they are more than the GHR and are unlikely to be recovered from the paying party in the event of a costs order in their favour.

It is for the solicitor to demonstrate to the court that the client has understood informed consent. It is then for the solicitor to decide whether they wish to recover any shortfall from the client.

How far you should go with that explanation is still relatively untested, but some guidance can be gleaned from Master Rowley’s decision in Edwards v Slater and Gordon UK Ltd in which Rowley concluded:

“The three reasons given for claiming the rates that are charged are (i) specialism, (ii) ensuring the work of this value remains commercial and profitable and (iii) providing an indemnity to protect the client against adverse costs.

“In my view, both reasons (i) and (ii) would justify higher hourly rates being claimed by Clear Legal from their clients than might be claimed by a less specialist or simply less commercially aware firm of solicitors. The purpose of the relevant paragraph in the client care letter seems to me to be written so that it can be referred to if necessary, on a Solicitors Act assessment of Clear Legal’s own fees by one of its clients.

“The presumption at rule 46.9(3)(c) is that costs will be presumed to be unreasonably incurred if they were unlikely to be recovered from an opponent and that prospect had not been explained to the client.”

The last point in particular should be heeded by practitioners.