In Zavarco plc v Nasir, the £36million question was: does the doctrine of merger apply to a declaratory judgment?

The Court of Appeal’s clear and unequivocal answer (merger “has no application at all to declarations”) would suggest that this was a simple point, however the experienced judges who grappled with the question in the lower courts reached contrasting conclusions. It remains to be seen whether the appellant will pursue the point to the Supreme Court in the hope of a different answer.

What is merger?

The doctrine of merger is the principle that the legal rights associated with a cause of action are extinguished when judgment is entered, and replaced by the legal rights arising from the judgment.

Merger is a companion to, but distinct from, various procedural doctrines which have been developed by the courts to prevent abuse of process and preserve the finality of litigation, namely res judicata, issue estoppel and the rule in Henderson v Henderson.

The simplest illustration of how the doctrine of merger works in practice is where judgment is entered on a claim for payment of a sum of money. From that point on, the judgment creditor’s right to payment (and interest) arises from the judgment. The underlying cause of action ceases to exist and the creditor cannot rely upon it as the basis for a second claim to seek further relief.

Prior to Zavarco plc v Nasir, little judicial consideration had been given to the application of merger to declaratory relief. The leading textbook on the subject, Spencer Bower & Handley: Res Judicata had, since the first edition was published in 1924, expressed the author’s view that a purely declaratory judgment would not qualify as a judgment granting relief and that merger would not apply, but had never cited any authority for that proposition.

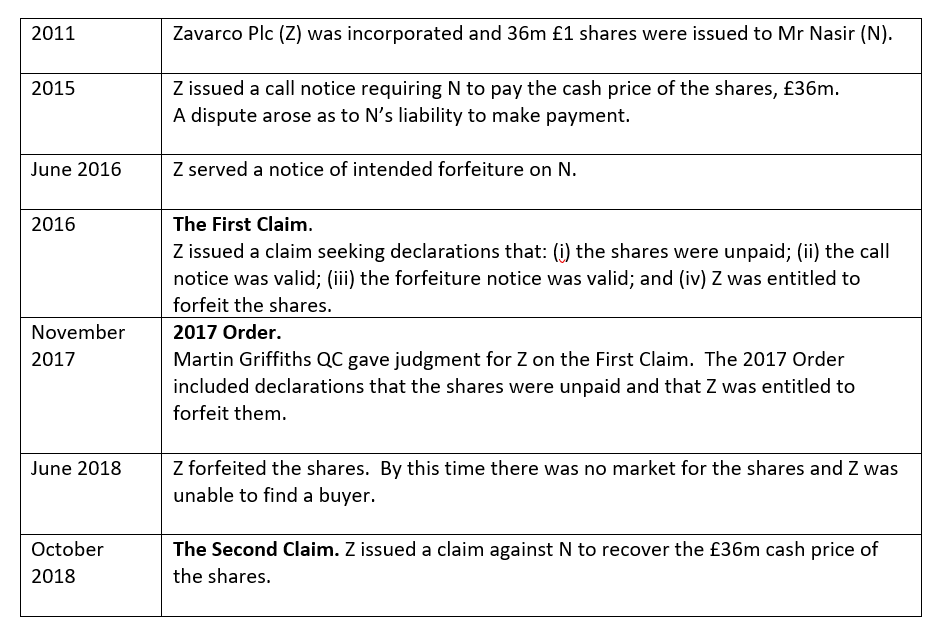

Zavarco plc v Nasir: sequence of events

First Instance Decision – 17 July 2019

The Second Claim was heard by Chief Master Marsh, who gave judgment for N. He concluded there was no reason to regard declarations as being materially different from other forms of final relief. Z’s cause of action had merged in the 2017 Order and the court had no jurisdiction to hear a further claim.

Birss J allowed Z’s appeal and directed that the Second Claim should be permitted to proceed.

Declaratory judgments could constitute final relief on a cause of action and it was therefore possible that a declaratory judgment could give rise to a merger. This would depend upon whether the effect of the declaration in question was to extinguish the underlying cause of action.

Where, as in the First Claim, the judgment declared the existence of a legal right, it did the opposite of extinguishing that right. It was possible that a further court might refuse to entertain a second action on procedural grounds as an abuse of process, but it would not be prevented from hearing a second claim by merger.

It was not appropriate to stay or dismiss the Second Claim on grounds of Henderson v Henderson abuse of process. Z had taken “a grave risk” in limiting the First Claim to declaratory relief, but looking at the conduct of the parties as a whole, it was obvious that enforcement of the obligation to pay the share price would or might follow the 2017 Order.

The Court of Appeal

Z appealed the decision on merger, arguing that Birss J had drawn an impermissible distinction between merger of a cause of action and merger of a right arising from a cause of action.

The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. In giving judgment, David Richards LJ (with whom Henderson LJ and Warby LJ agreed) agreed with Birss J’s conclusion that the 2017 Order did not extinguish the cause of action and additionally held that the doctrine of merger could never apply to declarations.

In reaching this conclusion, David Richards LJ made several observations about the nature and effect of merger.

- Merger is a rule of substantive law that is strictly applied. The court has no discretion as to its application.

- Merger applies where an obligation under the cause of action is embodied in, and replaced by a final order.

- Early authorities describe merger arising where a lesser right (a claim) is converted into an obligation of a higher nature (a final judgment).

- This analysis makes sense when applied to a judgment for a debt or damages, but not when applied to a purely declaratory judgment, which imposes no obligation but only confirms the obligation which already exists.

- Merger is a longstanding doctrine of common law. Declaratory relief is an equitable remedy which came into use subsequently, and was not in the contemplation of the judges who developed the doctrine of merger.

- There was no need to expand the doctrine of merger to cover declaratory relief. The other tools in existence were sufficient to tackle abuse of process.

In contrast to Birss J, David Richards LJ seemingly endorsed Z’s decision to limit the First Claim to declaratory relief, noting “In circumstances where Z was intending to operate the forfeiture mechanism it made good sense to resolve that issue by proceedings for a declaration without necessarily at the same time seeking judgment” (paragraph 23, judgment).

What are the practical ramifications of this decision?

On one view, Zavarco plc v Nasir is a decision on an obscure point which seldom arises in practice, as is evident from the fact that the view expressed in Spencer Bow & Handley has not been tested in a reported case in the past century.

However, the decision may have wider real-world consequences if it leads to more claimants issuing claims limited to declaratory relief, in the expectation that further remedies can be pursued at a later date. This approach may be attractive to claimants who wish to reserve their position as to the ultimate remedy and/or to avoid costs, not least the issue fee payable on money claims.